Gathering

Human beings have foraged for survival for thousands of years. Gathering nature’s bounty from the woods, both to eat and provide shelter, is a primordial human activity. I have always loved searching in forests to find beautiful trees to create special bowls, furniture, and houses, just as I have enjoyed hunting for such delicacies as morels and ramps to cook special meals. The land-to-hand process offers an innately satisfying means of survival, in harmony with our surroundings.

Selecting

The Oak Hill Road house will be largely fabricated from local trees. We have cut eighty mature black walnut trees to construct the floors, furniture, doors, cabinets, and millwork. These trees have undergone a selection process that would impress even the most rigorous college admissions office. Color, density, patterns of grain, dimensions, and condition have all been carefully considered.

The first walnut tree we chose was for building a table and ten chairs. We needed a tree with a wide, dense, short trunk and massive lateral branches that could provide strong curved grains as the branches transitioned out from the trunk. Walnut comes in many colors, depending on soil type and nutrients where the tree grew. The ideal tree would have a rich dark color to its heartwood, with very tight grain, which occurs in trees that have endured poor soil and lack of water. The tree needed to be at least two hundred years old to yield adequate dimensions. The size and color requirements for the chairs and table eliminated 99% of the thousands of available walnut trees we considered. Of the remaining hundred or so trees, damage such as trunk rot, interior animal nests, insect boring, and historical lightning scars reduced the number of possible contenders to twenty. Half of those trees were in locations too difficult to reach with equipment, leaving us with ten viable candidates. Five of the remaining ten trees had produced far fewer walnuts, indicating that they were in biological decline and thus preferable to remove from nature. Eventually, I would use all five finalists in the house. The one with the largest diameter trunk earned the distinction of becoming the table and chairs.

Cutting

A walnut tree that has spent two centuries developing into one of nature’s masterpieces should be treated with reverence. I try to make use of every piece, and to integrate the tree’s unique characteristics with my design. In order not to waste the lower part of the trunk, I make a single horizontal cut at grade using a chainsaw with a long, 48-inch bar. This usually causes the tree to bind against the saw, which necessitates employing a series of steel wedges to finish the cut.

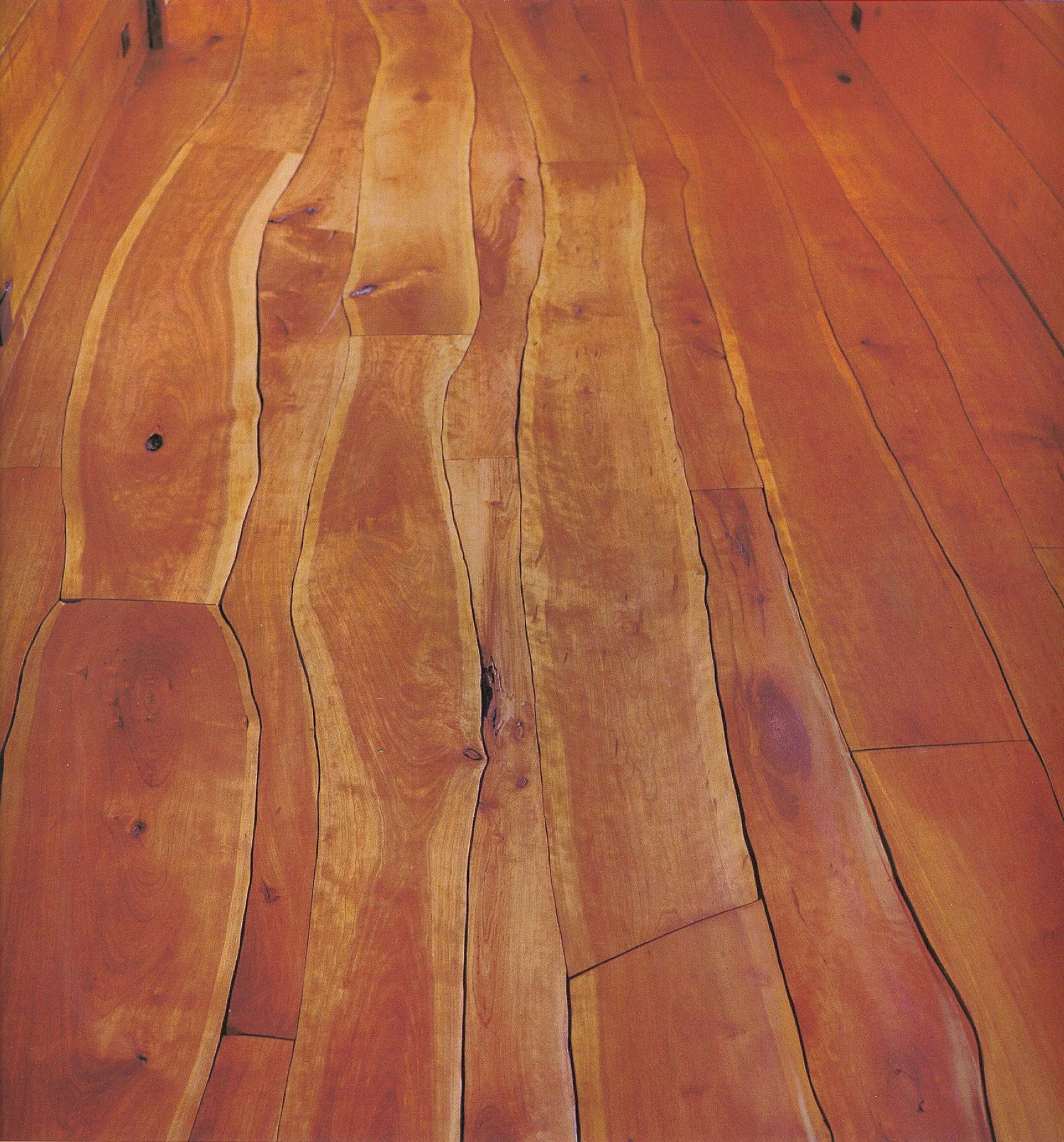

Sawing

We take the trunk and primary branches to our farm, where we have a Wood-Mizer sawmill that is capable of cutting planks 24 inches wide, 10 inches thick, and 40 feet long. Having my own sawmill allows me to cut a log deliberately to accommodate each part of a project. Every cut can be made to yield a piece of lumber with the ideal grain configuration. It is a slow process, but worth the time. This tree took about eight hours to saw, and yielded 550 board feet of exquisite local walnut.

Every tree is an adventure when you saw it. One walnut log created a disaster on the sawmill when the blades suddenly broke and the drive gears of the motor bound up with a bang. We had hit a large piece of metal inside the log, which turned out to be a horseshoe that had been hung on the side of the tree two centuries earlier. The tree had gradually grown around the horseshoe, eventually completely embdding it in the trunk. Marks on trees often bear witness to events that took place around them, such as fires, floods, or droughts, and it is not uncommon to find a nail or bullet inside a tree, but such a large object ingrained in the wood and capturing a moment in history was worth the damage to the sawmill and will certainly find a prominent place in the house, reminding us of the distant past the wood enshrines.

Drying

After the logs have been sawn into planks, each piece of lumber is waxed on its end grain to prevent water from leaving the boards too quickly. The boards are then placed in a barn, stickered to allow airflow between each plank, and air-dried for at least one full year for every inch of board thickness. Most commercially-sold walnut is dried in a kiln, which mandates a steaming protocol inside the kiln every two days for almost two months in order to prevent surface cracking. The repeated steaming of the wood neutralizes its color, eliminating the rich contrasts that make walnut so special. The advantage is that kiln-drying is much faster than air-drying. Some of the wood we cut for this project was six inches thick, which meant that we needed six full years to dry it. Six years seems like a long time in the demanding schedule of most projects; I see it as simply the physical reality of using this particular wood.

Replacing

When the tree has fallen, we cut off the pieces we are not going to use and heap them into a messy, intertwined pile. The squirrels promptly make nests in the dense jumble of branches because it protects them from predators. They hoard walnuts from the tree deep in the center of the pile. During the winter, many of the squirrels are killed, which leaves their walnuts to germinate in the spring. The young saplings shoot up for the sunlight, through the pile, during their first few years of life. The tangled branches protect the saplings from deer, allowing them to grow to a height above the browse line. As the pile slowly disintegrates, it creates the nutrients that the young trees need to grow. Roughly a decade after cutting the tree, when the saplings have reached a height of about ten feet, we identify the strongest sapling and cut down the others around it to give the chosen tree the advantage of growing without competition. Genetically, the young tree is the actual offspring of the older tree that I felled. I hope someday someone will chance upon this replacement tree, and decide it is the perfect one to create something special.