Turning a bowl on a lathe is a gratifying woodworking activity that even a child can do. With little skill or effort, a wooden object can be produced from a single piece of wood, with no joints or other complexities, its form a simple, basic gesture, its purpose friendly and practical. At age 11, I turned my first bowl, a sugar bowl with a lid, for my mother. I have since turned dozens, mostly salad bowls, for myself, friends and family - and have also taught many people to turn their own bowls. The best wood to use is a burl, a growth that sometimes arises on trees, believed to develop as a result of stress, such as an injury or fungus. The burl’s grain is twisted and interlocked, wildly non-directional, which makes it visually dramatic as well as strong and durable, with no tendency to split.

Whenever I walk in the woods, I keep an eye out for burls. You can never be sure what you will find inside them until you begin the turning; the colors and patterns reveal themselves continually throughout the process. I have experienced occasional disappointments, when the bowl’s shape and markings failed to live up to my hopes, or the bowl exploded on the lathe, but most of my turnings have entailed a delightful exposition of the wood’s natural beauty as the vessel took shape.

Five years ago, I embarked on an extreme adventure in woodturning. A violent windstorm had blown over a huge Circassian walnut tree in an orchard in Turkey, exposing an enormous underground root burl that weighed over a thousand pounds and measured almost six feet in diameter. A friend in Canada who sells fine hardwoods asked me if I would like to buy it. Unsure of what might lurk within and of what I might concoct with such a mysterious treasure, I said yes.

The object that arrived on my doorstep looked like an alien pod apt to hatch in the night.

I considered making table tops, cabinets, and various other sensible projects for the new house, before deciding to abandon practicality and turn a very big salad bowl. Among the obstacles to my intended venture, I didn’t own and had never even seen a lathe that could handle anything close to that size.

The US Navy came to my rescue with one they had built in the 1920s to make patterns for large battleship guns. It weighed several tons. Mounting the bowl on the lathe required devising a faceplate of one-inch-thick steel with 36 holes for ¾-inch by 6-inch lag bolts to connect the burl to the lathe. The new metal faceplate weighed 1500 pounds with the raw burl bolted to it.

The turning took ten days. Time was of the essence because wet, non-native wood can be destroyed quickly by local fungi. I broke chisels, lathe bearings and mounting bars because no cast iron parts could withstand the vibration forces of something this heavy. I needed to fabricate tool rests of reinforced hardened steel. It then became apparent that the rim speed of a six-foot diameter object turning at 300 rpm is considerably faster than that of the two-foot diameter objects to which I was accustomed. The increased speed created so much friction, my chisels melted. Slowing everything down required special engineering to alter the electrical phase impulses entering the lathe motor. Even at a relatively slow turning speed, the burl, which was eccentric in density, shook violently and threatened to rip itself off the lathe. I added specially cast weights to the burl to balance its rotation, in a manner similar to balancing the wheel of a race car. Yet despite all the measures I took to ensure safety in the process, few people dared to join me in - or even near - the building whenever I turned on the lathe, not unreasonably envisioning the bowl flying off and smashing through the barn walls.

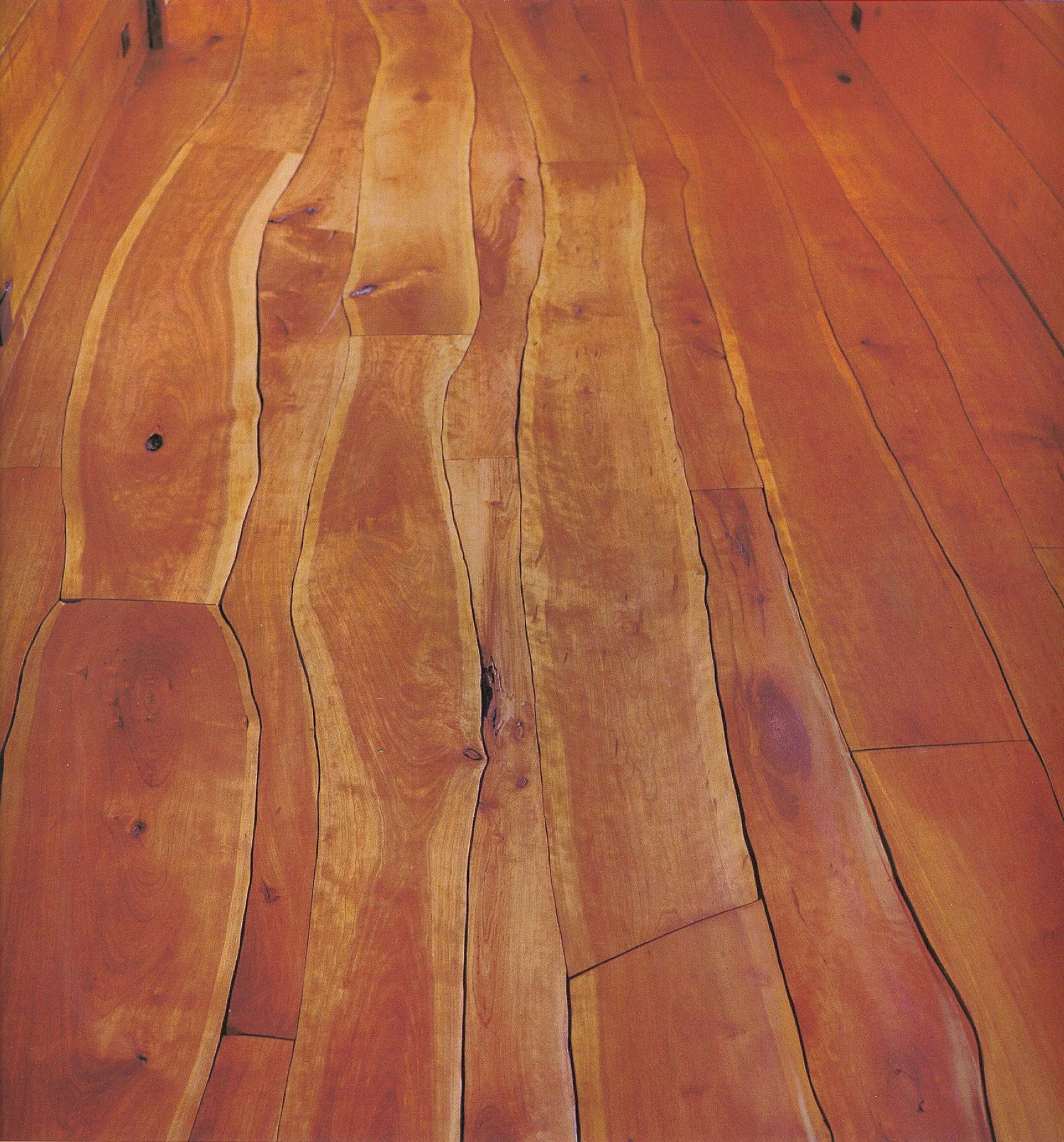

Turning the bowl posed perils and required ingenuity at every step, but the spectacle that eventually came to light made the effort worthwhile to me. The grain inside the burl emerged as wild and chaotic near the perimeter, and grew gradually more geometric towards the interior, with the cylindrical annual rings disappearing into darkness in the center. This graphic transition from anarchy to order created infinite visual depth in an object that was only nine inches deep. In addition, as I started to peel off the bark, I discovered a wonderful exterior texture that looked like hundreds of little cones making up an unearthly landscape. I wanted to preserve this natural texture in as many places as possible while still making enough of a mark to define the shape of a circle. I always tried to allow the spirit of the wood to dominate the design, to sustain the right balance between my intervention and the inherent form of the burl. The interface between the manipulated and the natural surfaces manifests the vitality of man and nature working in concert.

The bowl is now complete, sanded and finished with a mixture of linseed oil and beeswax from our apiary. At just under six feet in diameter and 320 pounds, I feel confident that if we ever need to make a salad for three or four hundred people, we have the perfect vessel. Until then, we will put the bowl on the living room floor of the Oak Hill Road house as a place for our two cats to enjoy the afternoon sun.