The global economy creates valuable opportunities. In the field of architecture, an exhaustive palette of readily available, mass-produced building materials makes construction cheaper and easier than ever before. Windows, doors, roofing shingles, floor tiles – every part of a structure – can be ordered and shipped from anywhere to anywhere on the planet. Architects all over the world use identical computer programs to assemble designs with a speed, accuracy, and uniformity that have driven drafting boards and T-squares into nearly complete obsolescence. All that efficiency saves money and prevents mistakes, but I am troubled by the attendant sacrifices.

The alternative to globalized architecture that I have embraced on Oak Hill Road is my version of vernacular architecture, which entails employing local materials and designing in response to local conditions, needs, and customs. From the ancient indigenous tribes’ adobe pueblos nestled into majestic canyon walls in the American Southwest, to the nineteenth century industrial kilns of upstate New York, resourceful societies have developed elegant, commonsense solutions to their particular habitation needs without recourse to Philippine mahogany, high-voltage transmission lines, or AutoCAD. Those artisans can lie in their graves feeling proud of the ingenious architectural responses to their distinct territories and moments in history – the vernacular identities – that they created. The place and time in which we live now calls for a new vernacular.

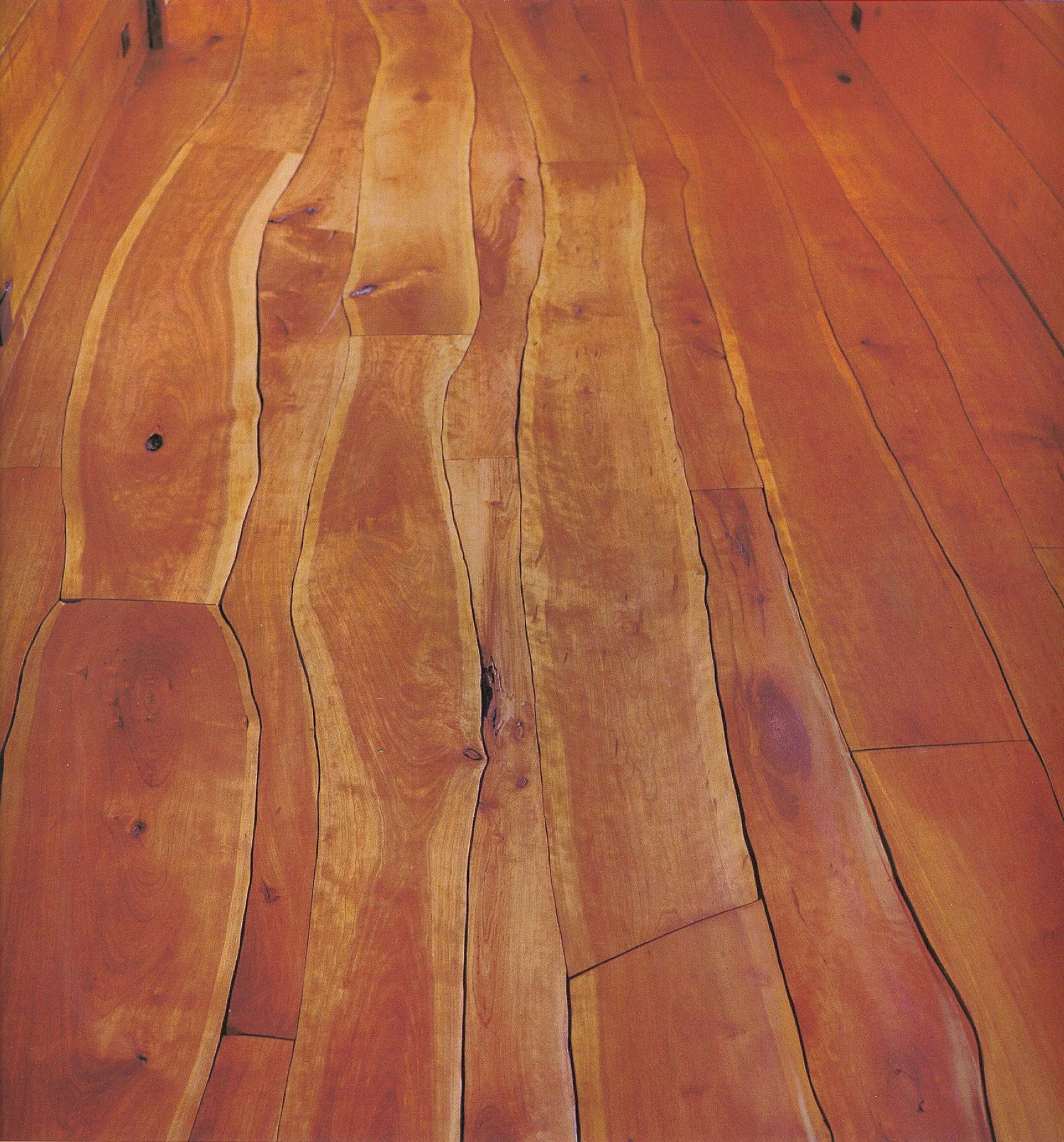

The most urgent challenge that today’s architecture should undertake is carbon neutrality. The use of local materials – an element of vernacular architecture by definition – reduces energy costs associated with transportation. As discussed in earlier journal entries, local stones and wood will be major components of the Livingston house. A less obviously regional material widely available in our modern society comes not from nature but rather from the extensive previous generation of buildings all around us that are in the process of being demolished. Reusing materials from nearby discarded buildings decreases not only the carbon footprint of manufacturing and transporting, but also diminishes the amount of waste consigned to landfills. Among the materials I have harvested from derelict buildings, copper is my favorite.

The copper for Oak Hill Road comes from various neighboring structures that were originally built in the early 1900s. Decades of exposure to the elements at myriad angles and positions has caused the copper to weather inconsistently, and produced a lavish array of colors and textures. We carefully removed the old roofs and recut the copper sheets to create strikingly patterned exterior siding.

In addition to wonderful aesthetic qualities, the material also offers meaningful energy efficiency. The color and pattern of the copper plates have been designed to allow for the maximum yield in reusing an old material; there is less than five percent waste in the transition from the old roofs to the new siding. The crimping, cutting, and fastening details involve human labor but little energy to accomplish. While new copper has a high embodied carbon footprint due to its manufacturing process, the reused copper’s embodied footprint is effectively zero because it has been fully depreciated into its life on previous buildings. Moreover, the material is timeless and will never rot or need to be painted, further reducing its carbon footprint. Copper also has a high capacity for absorbing and retaining the sun’s heat during the winter, which reduces the heating requirements of the building.

Unlike copper, which never requires maintenance or replacement, painted wood necessitates hefty financial and energy expenditures for re-painting every three to five years and for maintenance every ten years or so to replace rotten components. Nevertheless, architects and homeowners in this region cling to it. Why? Perhaps the profession of architecture has evolved too far.

Vernacular architecture is sometimes called “architecture without architects.” The buildings are designed and constructed by the people who inhabit them. Those people concern themselves with functionality, efficiency, and ease of use, and their design aesthetic seeks harmony with their surroundings. They would never clad a building with a material so impractical as painted wood. In fact, the entire concept of a wooden box sticking up out of the land, neglecting to take advantage of the ground’s thermal benefits through earth berming, would be anathema to them. Today’s architects, on the other hand, have grown progressively more distant from the physical reality of construction and rarely know how to build with their own hands. The hammer was replaced by the pencil, and the pencil has been replaced by the computer. Technologies, tools, information, and materials fly around the planet so effortlessly, it seems more sensible to devise plans sitting at your desk, clicking buttons, than to step outside your door and see what’s available around you. Architects no longer lead through knowledge of craftsmanship, historical styles trump common sense, and the global virtual reality has eclipsed local reality.

A century from now, I hope any historian looking at the house on Oak Hill Road would be able to say that it expressed an appropriate vernacular identity for its place and time.