During the 1980’s, my architectural firm received a request to design a doghouse for Guiding Eyes for the Blind. The doghouse was to be part of an exhibition at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York, along with doghouses designed by other architects which would then be sold at auction to purchase puppies that would be trained to assist blind people in their daily lives. There was considerable competition among the various architectural offices designing the doghouses. No one wanted to be the creator of the doghouse that earned the lowest bid at the auction. Our doghouse was elegant and beautifully crafted. It commanded the exhibition gallery and immediately spoke to anyone looking at it of architectural sophistication. I felt proud when it brought the highest price at the auction and turned out to be the most photographed by the press… clearly a success.

Twenty years elapsed, and I saw the doghouse again. It was owned by an individual who prized it as part of an American folk art collection. I looked carefully at it and didn’t understand it, even though I had been involved in its creation. After spending some time analyzing what felt amiss, I came to the conclusion that we hadn’t cared enough about the dog. We had designed the doghouse for people and for the press, when we should have designed the doghouse to respond to its tenant. I resolved not to make the same mistake if ever asked to design another doghouse.

Another decade went by and I stumbled across a photo of the doghouse while cleaning my office. My sympathy for the dog had not diminished, but once again I reacted to the doghouse differently. I realized the design should have reflected and responded to the unique relationship between the dog and his owner. The emphasis on visual beauty in an object owned by a person who couldn’t see it and inhabited by a dog who couldn’t comprehend it, exceeded irony. In fact, of the twelve doghouses designed by well-known architects in that exhibition, none of them responded to the guide dog and blind person’s particular relationship, needs, and attributes. Surely we, as a profession, should be capable of dealing more effectively with architecture as a non-visual experience.

I have no plans to design another dwelling for a guide dog, but the doghouse epiphanies raised my awareness about how little architecture reaches out to the non-visual senses. I would like to create moments in the Oak Hill Road house where the touch of an object is as rewarding as the sight. The floor offers one such opportunity. Floors tend to be flat and unexciting to touch, but human feet are sensitive.

Most people can recall the childhood pleasure of walking on a beach, with the receding tide leaving patterns of ridges in the sand. I remember closing my eyes and allowing my feet to follow the patterns. Without sight, my other senses sharpened: the sounds of the birds became more intense, the lick of the waves more sensuous, the dampness of the fog more penetrating, the smell of the salt and seaweed more vivid. I then opened my eyes to see if the ridges in the sand, my memory of their pattern, and the touch of my feet had brought me where I expected. They had. I would like the floor of my house to provide a similar adventure.

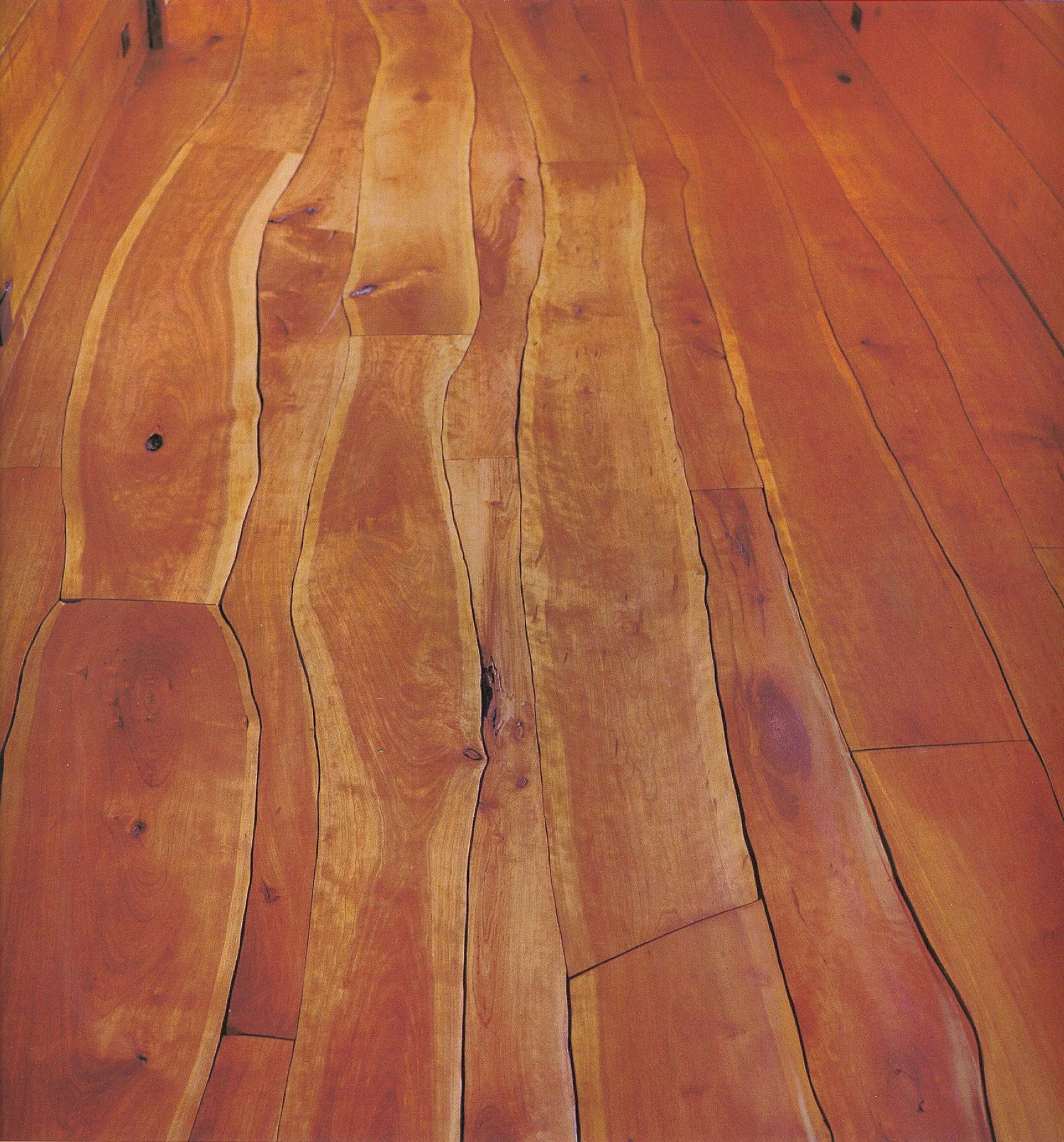

To that end, I have cut twenty large walnut trees, milling them as 1½-inch-thick, live-edge boards, meaning that they have not been cut to have parallel edges but instead have retained the shape of the tree. The mantra of Montessori education, “follow the child,” advocates allowing each child to excel by molding the teaching to the individual child’s natural interests and capabilities. Likewise, I try to adhere to the woodworking mantra of “follow the tree.” Both children and wood can reach their full potential by capitalizing on their inherent attributes, and not using a cookie-cutter approach.

Rather than allowing the machines that have developed over the past two centuries for cutting straight, flat boards, to dictate the shape of my wood, I have -- as with the ten chairs described in an earlier journal entry -- maintained the trees’ contours. I will scribe the boards to one another, matching their individual curves, and then crown each board to be thicker in the center than at the edges, so that the floor undulates like the rippled sand on the beach. The floor will be installed in a pattern that leads you places by sight and touch, to rooms and to exterior paths and views, down the river and behind the mountains.

Obviously, my passion for trees and wood runs deep. I love the look of beautiful wood, as well as the smell when it’s being milled, the sound of boards settling together, and the feel of a finely sanded surface. We always tried to teach our children that if they did something wrong, not to regard it as a mistake or failure, but rather as a “learning experience.” The doghouse was a learning experience for me. It taught me I should feature and share in my architecture the non-visual pleasures I know wood can offer.